The cost of efficiency (and why I hate fast escalators)

How efficiency/profit-driven mindset consumed the currency of dignity and respect.

One of the slower, longer escalators in Hong Kong: Midlevels Escalator. Still faster than escalators in other countries.

Credits to ncphotos

Of the many aspects of business school I could not understand, the one that seeped into my psyche until I had escaped Hong Kong was the obsession with efficiency for its own sake. Being a “hard worker” was apparently not a compliment but an insult because it implied they worked hard to compensate for the lack of results.

JIT supply chain models. Cheating the system, people for own gains (“through collaboration”). Supply and demand. Market efficiency. Every single thing was about efficiency. I sometimes wonder what risk management majors had to say about this…

FS Streets’ “What they never told you about surprise” newsletter:

The costs of efficiency are everywhere -- just look at buying a car today. The 'just in time' inventory system of the manufacturers had only a few days of key parts in it. Of course, this is what every business school teaches. When supply chains got disrupted, factories were temporarily shuttered. All because a bigger buffer of these parts would show up on the balance sheet and look, at least temporarily, 'inefficient.'

The world is less predictable than we think. Random events happen with unpredictable results. The way to weather these is to have margins of safety, shock absorbers, and slack — in other words, inefficiency.

Inevitably, people will consider the latest disruption a fluke and no one will learn the lesson: When you remove the shock absorbers, you get the shocks. Don't win the moment at the expense of the decade.

…but the walls - literally and figuratively - will speak to you otherwise: to win the moment and think ‘long-term’ in an efficient way that takes you here to there.

Escalators. They take you here to there, so you don’t have to sweat waiting for elevators while running short on time or speeding up the stairs.

I believe Hong Kong has the fastest, and longest escalators in the world (long one, also known as Midlevel Escalators, officially made it to Guinness World Records). Hong Kong has a very efficient subway system by design and yet, these anxiety-inducing escalators are built into it as well. And people run on these escalators. It’s not enough that the speed’s jacked up, people have to run on them to meet the demands of a busy city life. Perhaps because their lives are busy, it is only necessary to squeeze every possible aspects of life to be efficient in order to live.

I don’t think it was always this way though. Prior to Midlevel escalator and handover in 1997, I imagine the city slightly slower in tempo. The effects of rapid transformation compounds slowly and manifests in people’s belief systems or culture years after the transformation; so during the time of transformation, I presume post-colonial mindset was dominant; the suppressed chaos about identity, “work hard play hard”, the desperate grasps at the freedom, creativity and expression bringing golden age of culture and arts to Hong Kong.

These are illustrated well in Wong Kar Wai’s films, like Chungking Express that includes scenes on the long escalator. I learned that he included the escalator scene because, while it’s symbolic of city’s impressive feats, it also represents shortened time between Central and Midlevels, which used to be stroll-or-hike-after-meal route for locals, thereby cutting down the shared time for people to bond and make memories together.

Central also happens to be the center of finance and banking. All the banks lining up the skylines of Hong Kong are there. Behind Central is Midlevels which is one of the famous places for the rich. Cutting the time between these two seemed eerily reflective of the state of free-market capitalism.

… these kinds of metaphors reduce us to achievement-driven and advantage-seeking entities, condemned constantly to self-optimise, as if our highest purpose is to be effective instruments. But effectiveness for effectiveness’s sake is an empty aim.

— You’re not a computer, you’re a tiny stone in a beautiful mosaic

You learn that there is no such thing as free lunch the very first day of economics class - that there are always trade offs and opportunity costs. The opportunity cost of incessant pursuit of efficiency is paradoxically, time, meaning and finally efficiency itself.

Efficiency is an optimization tool that aims to balance resources, but when this tool becomes an end rather than means, we can only recursively apply efficiency on efficiency to improve efficiency. We completely ignore other cognitive tools and meaning that initially drove us to pursue efficiency. We ignore the “don’t put your eggs in one basket” advice.

That design philosophy is very different from the way much of the rest of the U.S. economy operates. The pandemic has shown us the downside of perfectly optimized systems—from the supply of ICU beds and virus-sampling swabs to the availability of baker’s yeast. We’ve been desperately short of all three of those things precisely because we’ve spent years tweaking supply chains so we have only exactly the amount we can use right now, without the “waste” of empty ICU beds or idle swab-making machines. In that way, what has saved the internet—redundancy, flexibility, excess capacity—reflects not just a different design philosophy, but a different underlying economic philosophy as well.

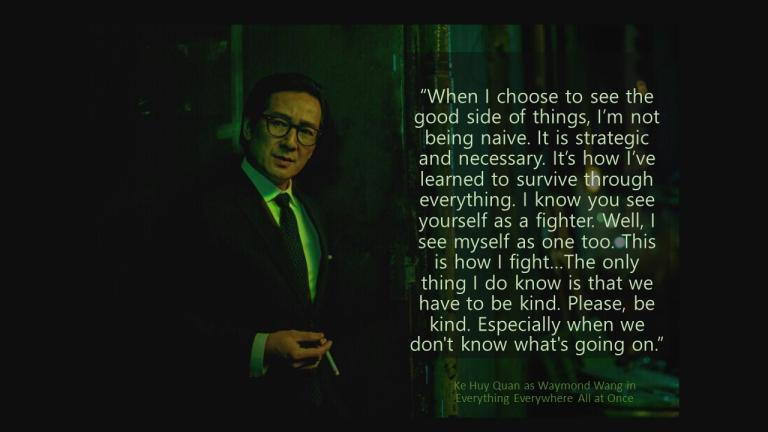

The case above shows how a perfectly optimal system cost many people’s dignity in their final hours. Efficiency or productivity cult functions in a similar way by failing to see others’ strategies or coping skills in life, mocking them as naive, lacking in strategy or emotional maturity (i.e why so childish?), and ultimately losing a valuable asset of information on how others learned to survive.

Being kind, unseen and quiet may seem to be the most inefficient form of living on the surface, but as seen from Waymonds’ lives in “Everything Everywhere All at once”, it turns out his strategy was the one that worked in the end. We may not be a Waymond saving the universe but we can save ourselves and those we love by learning to care less about appearing efficient, and instead starting to see the loved ones as they are, and how they managed to survive in such a harsh world where meanings are ephemeral and the whole world pressures them to conform.

In each case there’s value in saying, “I could have more and do more, but this is good enough.” But it’s such a rare skill. People don’t like leaving opportunities on the table, and it’s counterintuitive to realize that you’ll likely end up with more than those whose appetite for more is insatiable.

— Rare Skills

Other References, Quotes and Links

Getting Ahead By Being Inefficient

Why efficiency is dangerous and slowing down makes life better